ads1

Jealousy is a killer. Relationships end because of jealous conflicts and people kill other people because they are jealous.

Imagine this. You are at a party and

someone is friendly and you smile. Your partner thinks that you are

betraying her. Or your partner tells you a funny story about a former

lover and you feel threatened. You feel the anger and the anxiety rising inside you and you don’t know what to do.

Susan could identify with this. She

would glare at her partner, trying to send him a “message” that she was

really annoyed and hurt. She hoped he would get the message. At times

she would withdraw into pouting, hoping to punish him for showing an interest in someone else. But it didn’t work. He just felt confused.

At other times Susan would ask him

if she still found her attractive. Was he getting bored with her? Was

she his type? At first, he would reassure her, but then—with repeated

demands for her for more reassurance—he began to wonder why she felt so

insecure. Maybe she wasn’t the right one for him.

And when things got more difficult for Susan, she would yell at him, “Why don’t you go home with her? It’s obvious you want to!”

These kinds of jealous conflicts can end a relationship.

But, if you are jealous, does this mean that there is something terribly wrong with you?

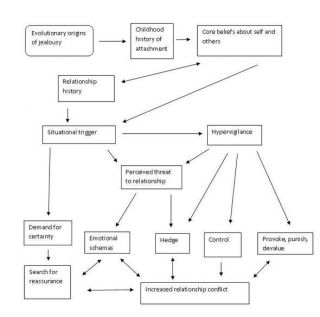

My colleague, Dennis Tirch, and I just published a paper on jealousy—and how to handle it. Click here to get a copy of the article that appeared in the International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. We describe a step-by-step approach to helping people cope with their jealousy.

Let's look at what is going on when you are jealous and how you can handle it.

Jealousy is angry agitated worry.

When we are jealous we worry that our partner might find someone else more appealing and we fear that

he or she will reject us. Since we feel threatened that our partner

might find someone more attractive, we may activate jealousy as a way to

cope with this threat. We may believe that our jealousy may keep us

from being surprised, help us defend our rights, and force our partner

to give up interests elsewhere. Similar to worry, jealousy may be a

“strategy” that we use so that we can figure out what is going wrong or

learn what our partner “really feels.” We may also think that our

jealousy can motivate us to give up on the relationship—so that we don’t

get hurt any more. If you are feeling jealous, it’s important to ask

yourself what you hope to gain by your jealousy. We view jealousy as a

coping strategy.

Similar to other forms of worry,

jealousy leads us to focus only on the negative. We interpret our

partner’s behavior as reflecting a loss of interest in us or a growing

interest in someone else: “He finds her attractive” or “He is yawning

because I am boring.” Like other forms of worry, jealousy leads us to

take things personally and to mind-read negative emotions in other

people: “She’s getting dressed up to attract other guys.”

Jealousy can be an adaptive emotion.

People have different reasons—in

different cultures—for being jealous. But jealousy is a universal

emotion. Evolutionary psychologist David Buss in The Dangerous Passion

makes a good case that jealousy has evolved as a mechanism to defend our

interests. After all, our ancestors who drove off competitors were more

likely to have their genessurvive.

Indeed, intruding males (whether among lions or humans) have been known

to kill off the infants or children of the displaced male. Jealousy was

a way in which vital interests could be defended.

We believe that it is important to normalize jealousy as an emotion. Telling people that “You must be neurotic if you are jealous” or “You must have low self-esteem” will not work. In fact, jealousy—in some cases—may reflect high self-esteem: “I won’t allow myself to be treated this way.”

Jealousy may reflect your higher values

Psychologists—especially psychoanalysts—have looked at jealousy as a sign of deep-seated insecurities and personality defects.

We view jealousy as a much more complicated emotion. In fact, jealousy

may actually reflect your higher values of commitment, monogamy, love,

honesty, and sincerity. You may feel jealous because you want a

monogamous relationship and you fear that you will lose what is valuable

to you. We find it helpful to validate these values in our patients who

are jealous.

Some people may say, “You don’t own

the other person.” Of course, this is true—and any loving relationship

with mutuality is based on freedom. But it is also based on choices that

two free people make. If your partner freely chooses to go off with

someone else, then you may rest assured that you have good reasons to

feel jealous. We don’t own each other, but we may make affirmations

about our commitment to each other.

But if your higher values are based

on honesty, commitment and monogamy, your jealousy may jeopardize the

relationship. You are in a bind. You don’t want to give up on your

higher values—but you don’t want to feel overwhelmed by your jealousy.

Jealous feelings are different from jealous behaviors

Just as there is a difference

between feeling angry and acting in a hostile way, there is a difference

between feeling jealous and acting on your jealousy. It’s important to

realize that your relationship is more likely to be jeopardized by your

jealous behavior—such as continual accusations, reassurance-seeking,

pouting, and acting-out. Stop and say to yourself, “I know that I am

feeling jealous, but I don’t have to act on it.”

Notice that it is a feeling inside you. But you have a choice of whether you act on it.

What choice will be in your interest?

Accept and observe your jealous thoughts and feelings

When you notice that you are feeling

jealous, take a moment, breathe slowly, and observe your thoughts and

feelings. Recognize that jealous thoughts are not the same thing as a

REALITY. You may think that your partner is interested in someone else,

but that doesn’t mean that he really is. Thinking and reality are

different.

You don’t have to obey your jealous feelings and thoughts.

Notice that your feeling of anger

and anxiety may increase while you stand back and observe these

experiences. Accept that you can have an emotion—and allow it to be. You

don’t have to “get rid of the feeling.” We have found that mindfully

standing back and observing that a feeling is there can often lead to

the feeling weakening on its own.

Recognize that uncertainty is part of every relationship

Like many worries, jealousy seeks

certainty. “I want to know for sure that he isn’t interested in

her.” Or, “I want to know for sure that we won’t break up.” Ironically,

some people will even precipitate a crisis in order to get the

certainty. “I’ll break off with her before she breaks off with me!”

But uncertainty is part of life and

we have to learn how to accept it. Uncertainty is one of those

limitations that we can’t really do anything about. You can never know

for sure that your partner won’t reject you. But if you accuse, demand

and punish, you might create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Examine your assumptions about relationships

Your jealousy may be fueled by

unrealistic ideas about relationships. These may include beliefs that

past relationships (that your partner had) are a threat to your

relationship. Or you may believe that “My partner should never be

attracted to anyone else.” You may also believe that your emotions (of

jealousy and anxiety) are a “sign” that there is a problem. We call this

“emotional reasoning”—and it is often a very bad way to make decisions.

Or you may have problematic beliefs

about how to feel more secure. For example, you may believe that you can

force your partner to love you—or force him or her to lose interest in

someone else. You may believe that withdrawing and pouting will send a

message to your partner—and lead him to try to get closer to you. But

withdrawing may lead your partner to lose interest.

Sometimes your assumptions about relationships are affected by your childhoodexperiences or past intimate relationships. If your parents had a difficult divorce because

your father left your mother for someone else, you may be more prone to

believe that his may happen to you. Or you may have been betrayed in a

recent relationship and you now think that your current relationship

will be a replay of this.

You may also believe that you have

little to offer—who would want to be with you? If your jealousy is based

on this belief, then you might examine the evidence for and against

this idea. For example, one woman thought she had little to offer. But

when I asked her what she would want in an ideal partner—intelligence, warmth, emotional closeness, creativity,

fun, lots of interests—she realized that she was describing herself! If

she were so undesirable, then why would she see herself as an ideal

partner?

Use effective relationship skills

You don’t have to rely on jealousy

and jealous behavior to make your relationship more secure. You can use

more effective behavior. This includes becoming more rewarding to each

other—“catch your partner doing something positive.” Praise each other,

plan positive experiences with each other, and try to refrain from

criticism, sarcasm, labeling, and contempt. Learn how to share

responsibility in solving problems—use “mutual problem solving

skills.” Set up “pleasure days” with each other by developing a “menu”

of positive and pleasurable behaviors you want from each other. For

example, you can say, “Let’s set up a day this week that will be your

pleasure day and a day that will be my pleasure day.” Make a list of

pleasant and simple behaviors you want from each other: “I’d like a

foot-rub, talk with me about my work, let’s cook a meal together, let’s

go for a walk in the park.”

Jealousy seldom makes relationships

more secure. Practicing effective relationship behaviors is often a much

better alternative. For more information about how to improve your

relationship, click here. Below is an outline from the Leahy and Tirch (2008) article on the nature of jealousy.

Source: Robert Leahy